Economics

The Fed should stand pat on further interest rate hikes at this week’s meeting: Inflation is easing even as the labor market remains strong

Inflation and all of its main drivers sharply decelerated in the last half of 2022. This was the case even though the pace of economic growth accelerated…

Inflation and all of its main drivers sharply decelerated in the last half of 2022. This was the case even though the pace of economic growth accelerated in the second half of the year and unemployment remained very low.

The Federal Reserve’s “dual mandate” is meant to balance the risks of inflation versus the benefits of fast growth and low unemployment. Right now, the benefits of low unemployment are enormous, and the risks of inflation are retreating rapidly. If the Fed lets the current recovery continue apace by not raising interest rates further at this week’s meeting, 2023 could turn out to be a great year for the economic fortunes of American families.

It is time for the Fed to stand pat on interest rate increases and wait to see how the lagged effects of past increases enacted in 2022 will filter through to the economy. Continuing to raise rates in the early stretches of 2023 will be a clear mistake and pose an unneeded threat to growth in the next year. In particular, the Fed should note the following:

- Rapidly decelerating inflation in the last quarter of 2022 happened even in the absence of a strong disinflationary effect everybody knows is coming quickly in 2023: falling housing cost inflation.

- Wage growth is normalizing quickly—average wage growth for the last three months of 2022 relative to the previous three months was just 4.3% at an annualized rate. This is down from a peak growth rate of 6.1% seen earlier in 2022.

- Crucially, this proves that wage growth can normalize without a steep rise in unemployment. This should settle one of the key debates over monetary policy going forward.

- Corporate profit margins—one of the key drivers of inflation—will likely stabilize or even contract in the coming year. This means labor’s share of income will rise, which has the potential to absorb any wage growth that exceeds its long-run targets for years to come. Past experience suggests strongly that this is not just a vague hope, but will actually happen.

Housing costs are the shoes that haven’t dropped yet

Much of the acceleration in core inflation seen in late 2021 and 2022 was in housing. However, even as overall core inflation decelerated strongly in the last quarter of 2022, housing costs did not. That is changing—all close observers of real estate markets are flagging industry data that show beyond any real doubt that housing cost inflation (both prices of homes and rental costs) is falling rapidly.

However, because of well-known issues in how housing costs are measured and reported in official government price indices, this lower inflation will not be seen in official data until later in 2023. But they are all but guaranteed to show up.

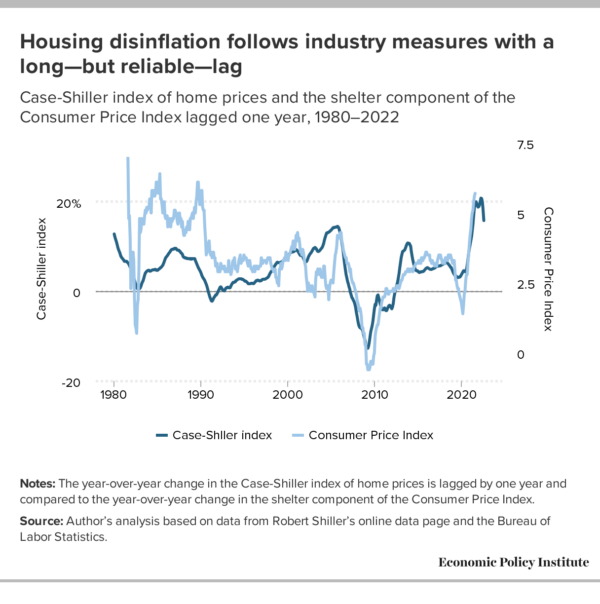

Figure A below, for example, shows the tight fit between one often-cited industry measure of housing prices (the Case-Shiller home price index) lagged one period and the current reading of shelter inflation in the Consumer Price Index. The tight fit between these measures shows, for example, that developments in the Case-Shiller index in 2022 are likely to predict shelter inflation in 2023. Because this relationship indicates that a dose of significant disinflation is clearly in the pipeline even as overall inflation measures are normalizing, the Fed should feel far more comfortable standing pat on further rate hikes.

Wage growth has normalized quickly

A key concern of inflation hawks over the past year has been rapid growth in nominal wages. They have called attention to the relatively uncontroversial fact that an overall price inflation target of 2% is consistent with nominal wage growth of only about 3.5% when the economy is in equilibrium, and that this wage growth has been as high as 6.1% in 2022. However, there are plenty of reasons why this is misleading about the threat that fast nominal wage growth might pose to inflation today.

For one, wage growth has been decelerating rapidly. In the last three months, annualized wage growth has been running at a 4.3% (annualized) rate, a pace consistent with inflation below 3%. This represents a sharp deceleration even as the unemployment rate has remained very low.

Figure B below shows the unemployment rate and the three-month change (expressed as an annualized rate) of wage growth in recent years. The dashed lines smooth out the extreme ups and downs of both unemployment and wage growth during the pandemic recession and early recovery. (In the case of wage growth, these extreme ups and downs were largely due to compositional effects that gave very little information about the actual state of labor market tightness one way or the other.)

Falling corporate profit margins will put further downward pressure on prices in 2023

The claim that 3.5% wage growth is the fastest rate consistent with 2% inflation “in equilibrium” assumes that the share of overall income claimed by workers’ pay rather than corporate profits remains constant. However, wage growth can exceed 3.5% for a spell of time while still being consistent with 2% inflation if the labor share of income is allowed to rise. Importantly, the labor share of income has shrunk significantly throughout the recovery from the COVID-19 recession. This means that by definition the economy is not in equilibrium on this score, and just returning to the pre-COVID labor share of income would allow lots of wage growth without feeding through to price inflation.

This is, of course, the mirror image of saying that rising corporate profit margins have been a prime driver of inflation throughout this business cycle, but these margins will stabilize or even contract in the coming year, clearing the way for non-inflationary wage growth.

Some have argued that, while arithmetically true, claims that a rising labor share of income will absorb some of the inflationary impact of faster wage growth are just wishful thinking. Empirically, that’s flat-out wrong. In essentially every single business cycle since World War II, when unemployment moved close to pre-recession levels late in recoveries, further labor market tightening has been strongly associated with a rising labor share of income. This means that the rising labor share absorbed lots of potential inflation and kept it from happening.

Figure C below shows the slightly complicated cyclical dynamics of the labor share of income over business cycles. Its local peak occurs during recessions, as profits fall faster than wage incomes in the recessionary phase of the business cycle. But the labor share trough tends to follow quickly after its recessionary peak, and the latter stages of business cycles universally show a rapid rise in the labor share. Sometimes this labor share increase is snuffed out by another recession before it regains its previous peak, but the pattern is very clear: As labor markets remain relatively hot, much of the potential inflationary impact of this tight labor market is absorbed by a rising labor share of income. This post provides some regression evidence that further labor market tightening is associated with labor share increases.

Just how much room do we have from potential labor share increases to absorb wage increases without generating upward pressure on inflation? Figure D below shows how long the pace of wage growth seen in the last quarter of 2022 could be sustained with inflation rising at 2% and the labor share of income reaching the pre-recession peaks it saw in 2019, 2007, and 2000, respectively.

Essentially, this figure shows that labor share peaks seen in the past few business cycles provide many years of room for wages to grow as fast as they are currently without pushing inflation above the Fed’s 2% target. If we use 2019 as the benchmark, we could see current wage growth being fully absorbed by a rising labor share until the second half of 2026. If 2007 is the benchmark, this can happen until the end of 2029. Finally, if 2000 is our benchmark, wage growth at its current pace is possible without seeing inflation above 2% all the way until the end of 2036.

Conclusion

The balance of risks faced by the Fed has moved decisively away from spiraling inflation. Key sources of disinflation—especially housing costs and a rising labor share of income—have yet to kick in, and inflation still decelerated rapidly in the last quarter of the year. The Fed should stand pat on interest rate increases. If they instead insist on raising rates, this will pose a dire threat to what could be an excellent 2023 for the economic prospects of America’s working families.

inflation

monetary

markets

reserve

policy

interest rates

fed

monetary policy

inflationary

Argentina Is One of the Most Regulated Countries in the World

In the coming days and weeks, we can expect further, far‐reaching reform proposals that will go through the Argentine congress.

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

Crypto, Crude, & Crap Stocks Rally As Yield Curve Steepens, Rate-Cut Hopes Soar

A weird week of macro data – strong jobless claims but…

Fed Pivot: A Blend of Confidence and Folly

Fed Pivot: Charting a New Course in Economic Strategy Dec 22, 2023 Introduction In the dynamic world of economics, the Federal Reserve, the central bank…